|

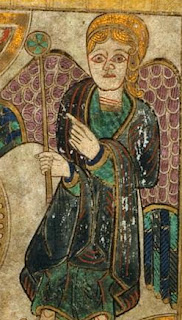

| The Arrest of Christ from the Book of Kells |

One segment of Irish society that had no honor price was the ‘cimbid’. A cimbid was a prisoner who had committed a crime worthy of death. They were usually kept bound until they were handed over to be killed by the party whom they had offended. People could do what they wanted to a captive cimbid without any legal consequences. There was no honor price to pay for a cimbid. A cimbid was both a social pariah and an object of wrath. According to the early Irish law tract Críth Gablach, a cimbid was to executed “cen aurlúd ”, that is, without a pricking of the conscience.

Early medieval Irish scribes looked for Irish parallels to important words or expressions they found in the Scriptures. They would gloss their Latin bibles with Irish words to help bring out the meaning of the text in a way that resonated for them. For example in Romans 9.3 where Paul mentions being “accursed and cut off”, an Irish scribe wrote under these words, ‘a cimbid’. Our scribe could think of no better way to explain someone accursed and cut off than the cimbid, a man with no honor price.

Another Irish scribe read in Matthew 27.26, “then [Pilate] released for them Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified” then he noted in the margin of his Bible, “dilse cimbetho” i.e. the penalty of a cimbid (Turin MS, Bibl. Naz. F vi 2) To a medieval Irish Christian that must have been hard to read. The death of a cimbid was not heroic, it was humiliating. To see Christ as willing to suffer the death of a cimbid was to marvel at the awe-inspiring love and humility of God. Not only was Christ leaving aside the honor price that was His due from all those who had sinned against him (cf. Phil 2.1-11), but He voluntarily died in the place of the real cimbid, fallen man. As an ancient Irish commentary describes it, “His reproach has removed our disgrace. His bonds have set us free. By the crown of thorns on His head we have gained the diadem of the kingdom.”