|

| The Arrest of Christ from the Book of Kells |

Monday, April 16, 2012

Irish Gloss on Matthew 27:26

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

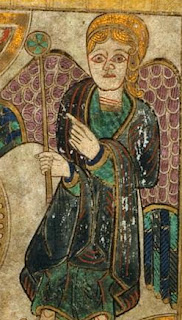

Oriental Influences in the Early Irish Church

|

| Ballycotton Brooch, 8th cent. |

Back in 1875 in Ballycotton in Co. Cork, Ireland, a silver brooch was unearthed from a bog. It was dated to the eighth century AD. It was clearly a Christian cross, but what was strange about it was the inscription in the center. It was in Arabic and contained the word Allah. The rest of the inscription is unclear, it is thought either to read, "we have repented to God" or "If God wills". Either way, it is striking to consider the possibility of Arabic speaking Christians in Ireland at this time.

The evidence for oriental Christians in Ireland is fragmentary but there are several fascinating mentions of Egyptian and even Armenian Christians in Ireland from around the same time as the Ballycotton brooch.

In an early Irish litany attributed to Óengus of Tallaght (fl. 800) there is mention of seven Egyptian monks (manchaib Egipt)

buried in Uilaigh, Co. Antrim. The discovery in 2006 of an Egyptian style book binding (with papyrus lining) with the Faddan More psalter in a Tipperary bog has given support to the theory of Egyptian Christians in Ireland around the year 800.

|

| Litany of Óengus mentioning Egyptian Monks in Ireland |

The arrival of Christians from Ummayad Spain or Egypt does open up some interesting questions relating to the character and theology of the early Irish church. Telepneff has suggested that certain Irish ascetic practices once thought to be exclusively Irish can actually be traced back to Egyptian sources. One example is the so called crux-vigilia. This ascetic practice involved praying for hours on end with your arms extended in the form of a cross. Verkerk mistakenly asserted that the cross vigil was exclusive to Irish monasticism, but as Telepneff has correctly shown the practice was followed by Egyptian monks like Pachomios as early as the fourth century.

|

| Flabellum as depicted in the Book of Kells |

Discoveries like the Ballycotton brooch and the papyrus fragments in the Faddan More psalter have highlighted the role that oriental Christians, like the Copts, once played in the development of the early Irish church.

Sunday, April 8, 2012

Quem queritis ad sepulcrum?

Atomriug indiu

niurt a chrochtho cona adnacul

niurt a essérgi cona fhresgabaáil

niurt a thoíniudo fri brithemnas mbrátho.

Domini est Salus

Christi est Salus

Sulas tua, Domine, sit semper nobiscum!

Today I gird myself

with the power of Christ's birth together with His baptism

with the power of His crucifixion together with His burial

with the power of His Resurrection together with His ascension,

with the power of His descent to pronounce the judgement of the Day of Doom

Salvation is of the Lord

Salvation is of Christ

May your salvation, Lord, be with us always!

Thursday, March 29, 2012

1 John 5:7 and Irish Exegesis

Several Early Church Fathers commented on various verses from the Catholic Epistles but none ventured to write a verse by verse commentary on them. That was until the seventh century when a remarkable Biblical commentary was written in Ireland.

Several Early Church Fathers commented on various verses from the Catholic Epistles but none ventured to write a verse by verse commentary on them. That was until the seventh century when a remarkable Biblical commentary was written in Ireland. Friday, January 13, 2012

The Forerunner

"It is fitting for us to fulfill all righteousness (Matt 3:15). Notice how Jesus included John the Forerunner here in His call to fulfill all righteousness. This is the same John that leaped in his mother’s womb at the voice of the Theotokos. The same whose hands were not worthy to carry the shoes of our Lord let alone lay hold of the Christ and plunge him into the waters of baptism. The same who later doubted Jesus by asking, are you the Christ or should we wait for another? The obvious conclusion here is that though this same John was the greatest of all the Prophets, yet he was still a sinner, unable to fulfill all righteousness. Yea indeed, not only John but all men have failed to fulfill all righteousness. All that is, except one, the Only Begotten Son. And here is our lesson, it is only by participation in His life, in His death, in His burial, and in His resurrection that we too, like John the Forerunner, can see heaven opened and all righteousness fulfilled. As Hilary has written; 'For by Him must all righteousness have been fulfilled, by whom alone the Law could be fulfilled.' Though we doubt and fail, still it is fitting for us to fulfill all righteousness, if we are found in Him. It is fitting for us to fulfill all righteousness if we have been sealed with the Holy Spirit. It is fitting for us, for He and not ourselves has made us fit to do it with Him. By such could John bear witness of Him in life as well as death."

Monday, November 21, 2011

The Carmen Navale - The Boat Song

Columbanus was early Ireland’s greatest missionary. Together with a motley crew of pilgrims for Christ he traversed across modern day France, Germany, Switzerland and ended up in northern Italy where he spent the remaining years of his life correcting the heresies of the Arians of northern Italy with the cauterizing knife of the Scriptures. For Columbanus, life was a journey, a pilgrimage, a voyage of discovery and sometimes of hardship. Its final destination was union with Christ.

French historian Georges Goyau noted, the Celtic missionary genius had produced individuals of outstanding energy, it had given the world magnificent apostolic personalities. Of these Columbanus was probably the greatest. According to Léon Cathlin, Columbanus was together with Charlemagne the greatest figure of France in the early Middle Ages. Henri Petiot described him as a sort of prophet of Israel, brought back to live in the sixth century, as blunt in his speech as Isaiah or Jeremiah. And not to be outdone, Robert Schuman (former French Prime Minister and main architect of what would become the EU) lauded Columbanus as the patron saint of those who seek to construct a united Europe!

Journeying up the Rhine in 610, Columbanus and his disciples supposedly chanted his famous ‘boat song’. One can almost hear the Irish monks dig their oars into the Rhine’s formidable current as they struggle upstream. The poem compares the surging storm waters with the trials and struggles of the Christian life. Columbanus sees the tempests and storms of life overcome by the one who is in Christ. He frequently used the analogy of storms at sea as a picture for hardship and trials. The Carmen Navale is one of my favorite poems attributed to Columbanus. The translation is taken from Tomás Ó Fiaich's work 'Columbanus in his own words'.

Lo, little bark on twin-horned Rhine, From forest hewn to skim the brine, Heave, lads, and the echoes ring!

The tempests howl, the storms dismay, But manly strength can win the day, Heave, lads, and let the echoes ring!

For clouds and squalls will soon pass on, And victory lie with work well done, Heave, lads, and let the echoes ring!

Hold fast! Survive! And all is well, God sent you worse, he’ll calm this swell, Heave, lads, and let the echoes ring!

So Satan acts to tire the brain, And by temptation souls are slain, Think, lads, of Christ and echo Him!

Stand firm in mind ‘gainst Satan’s guile, Protect yourselves with virtues foil, Think, lads, of Christ and echo Him!

Strong faith and zeal will victory gain, The old foe breaks his lance in vain, Think, lads, of Christ and echo Him!

The King of virtues vowed a prize, For him who wins, for him who tries, Think, lads, of Christ and echo Him!

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Mise agus Pangur Bán! I and white Pangur!

|

| Greek paradigms in MS Stift St. Paul Cod. 86b/1 |

'Tis a like task we are at;

Hunting mice is his delight

Hunting words I sit all night.

'Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill will,

He too plies his simple skill.

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

In the hero Pangur's way:

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

'Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

O how glad is Pangur then!

O what gladness do I prove

When I solve the problems I love!

Pangur Bán, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

|

| Pangur Bán poem: MS Stift St. Paul Cod. 86b/1 |